Arthur Conan Doyle’s role in the evolution of the malevolent mummy trope was just as fundamental as Stoker’s contributions to the vampire, Stevenson’s to the werewolf, and Shelley’s to the science fiction monster. While “Thoth” succeeded in breaking the mummy out of its quaint roles as a romantic curiosity or a satirical mouthpiece, bringing it into the realm of somber fantasy and supernaturalism, “Lot No. 249” carried it over the threshold into abject horror.

The tale is almost single-handedly responsible for our perception of mummies as potential terrors – combined with the rumors surrounding the tomb of Tutankhamen, and the Bram Stoker horror novella, The Jewel of the Seven Stars – and was virtually adapted into one of Boris Karloff’s seminal roles as the nefarious immortal wizard (and revitalized mummy) Imhotep in Karl Freund’s splendid 1932 masterpiece, The Mummy. Seasoned with romantic elements of “Thoth” and Jewel of the Seven Stars, the picture was essentially co-written by Doyle, who had died two years before.

“Lot No. 249” is one of my favorite horror stories, because it combines the cozy sitting room atmosphere of Baker Street with the bucolic, intellectual setting of Oxford University, which is infused with a strange and terrible horror beyond the ken of Britain’s brightest and best. It is, however, far from a simple tale of terror, and has far more subtext – mostly sexual, cultural, and social – than the wildest tales of Poe or Hoffmann. The story is far more steeped in homoerotic overtones than “The Silver Hatchet,” brooding almost openly – without excuse or artifice – on the nature of British masculinity, and its ideal manifestation. The four main characters represent four elements of manhood: the “robust” athlete, the “robust” scholar, the effete victim, and the effeminate villain.

The story revolves around these men as they attempt to define and demonstrate their manliness, at times quite brazenly, fearing all the time that they might be – as Abercrombie Smith puts it – “unmanned.” The mummy in question is closeted away in the villain’s room, leading to speculation about his sex life (they assume it to be a kept woman), little imagining the truth: it is a revivified zombie employed to stalk, overwhelm, dominate, and strangle (a very suggestive means of murder) his male enemies.

It remains a brilliant commentary on Victorian manhood with all manner of fascinating symbolism surrounding closeted men, sexual victimhood, and the anxieties of passing as "manly" in a homosocial environment like all-male Oxford in 1884. For Doyle, who stewed over same-sex friendship, masculine rituals, and the “robust” sporting life, it is a vulnerable – if narrow-minded – thesis on the perils, pursuits, and anxieties of the single British male.

II.

The story begins at Oxford University where three students live in the three apartments stacked on top of each other in a medieval turret. Abercrombie Smith, an athletic, unimaginative medical student, lives on the top apartment. He is something of a blend between Watson and Holmes, enjoying solitude and pipes as much as a good boat race or boxing match. Below his apartment is the loathsome Edward Bellingham, a flabby, antisocial scholar of Eastern languages and metaphysics who has been travelling in Egypt recently. On the bottom story of the turret is the passive and anxious Monkhouse Lee, to whose sister Bellingham is engaged. The three apartments share a staircase, and while Smith remains engrossed in studies above, he often overhears encounters between his suite mates on the stairs or under his floorboards.

One evening Smith is talking with his friend Hastie, who seems to have a crush on Lee’s sister, and Hastie passionately warns Smith against befriending Bellingham, relating the story of how he once shoved an old woman into the river when she was too slow for his pace. Smith thinks Hastie is jealous of Bellingham’s engagement, but takes his words into consideration.

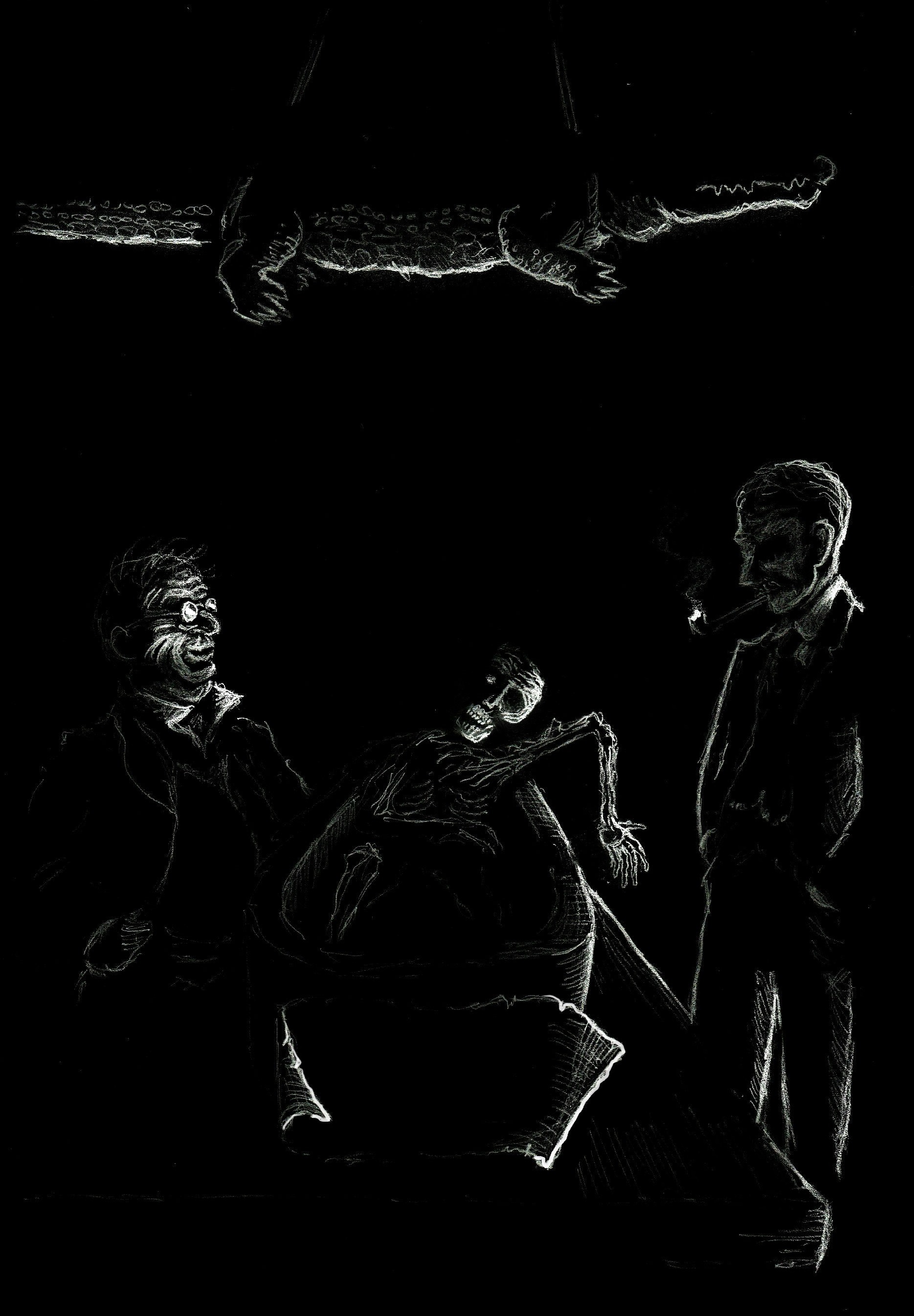

Later in the evening, he hears a strange hiss from below, followed by his door being flung open by a physically shaken Lee who begs him to attend Bellingham. Smith follows him to the middle apartment and finds Bellingham in a faint. His room is cluttered with all sorts of Egyptological relics – scrolls, urns, pottery, and even a crocodile suspended from the ceiling. In the middle of everything, however, is a table with a sarcophagus, and its occupant – a blackened, skeletal mummy – is laying inside it with one arm draped over the lid. Nearby is an ancient scroll, at Bellingham’s feet. Smith revives Bellingham, who attempts to laugh everything off, but is disturbed by Bellingham’s collection and his apparent dabbling in the occult.

As the weeks pass, Smith keeps hearing strange, mumbled conversations below him, and the turret’s man-servant slyly intimates that he hears walking inside the room while Bellingham is gone. Both assume that it is a woman (a strict violation of school rules) and that Bellingham is cheating on Lee’s sister. Soon after this, another student named Norton is attacked at night and nearly strangled by what he describes as an impossibly lean and strong figure. Norton had recently humiliated Bellingham, and while Smith doesn’t yet suspect that the mummy may be the attacker, he decides that his neighbor must somehow be responsible and begins watching his movements more closely.

A few days later, Lee informs Smith that he has moved out of the turret and is staying at a cottage. He warns him against spending time with Bellingham, whom he has warned against ever seeing his sister again, and encourages him to leave the turret, too. Smith asks him to explain his change in heart (before this, Lee was almost Bellingham’s disciple: a fawning, awe-inspired servant to the grotesque Egyptologist), but Lee claims that he can’t reveal the reason, only that Bellingham revealed something to him which he swore to keep secret. Smith claims that he knows the secret, which excites Lee, but when he claims that Bellingham is hiding a woman in his room, Lee shudders in disappointment and denies this. Later, Smith leaves his room and passes Bellingham’s, the door to which is open. In the dark Smith can see the upright sarcophagus, and thinks it looks empty.

That night Lee is rushed back to campus after being half-drowned in the Thames by an unseen attacker. Hastie and Smith successfully revive him, and Smith assures him that he now understands: in spite of his Holmesian materialism, he is now positive that Bellingham is animating the mummy and employing him as an assassin against his enemies. While it has not yet resulted in a murder, Smith feels duty bound to end its reign of terror. He bursts into Bellingham’s museum-like apartment and charges him with his suspicions. Bellingham tries to control his outrage, but is clearly seething with anger, he denies involvement in the Norton and Lee attacks and Smith leaves in a huff, letting Bellingham know that he is now a marked man.

The next day Smith leaves campus to visit his friend, Dr. Peterson, who lives in the country. As he passes through the moonlit lanes, he is startled by the sound of someone running behind him. Turning around he sees the black and skeletal mummy, eyes glowing like coals, and claw-like hand extended towards him. Smith sprints as fast as he can with the mummy in hot pursuit. He barely makes it to Peterson’s house and shocks the professor with his story. While Peterson isn’t quite convinced, he agrees to sign a paper witnessing Smith’s testimony in the event of his death.

The next morning, Smith bursts into Bellingham’s quarters and flashes a revolver in his face. Handing him a bonesaw, he gives him five minutes to cut up and burn the mummy before Smith plasters the wall with his brains. Clearly outraged but deeply frightened, Bellingham cooperates, destroying the mummy, which fills the room with the smell of resin, and begrudgingly follows it with the ancient scroll (which Smith has deduced contains the spell that awoke the mummy). Warning him that Peterson has his signed testimony, Smith demands that Bellingham depart and never return, which he does, disappearing to the Sudan. Smith, meanwhile, returns to his precious solitude and engrossing studies.

III.

Tragically, Doyle appears to have had a word limit to meet, because the story which begins sailing smoothly ends on a clunky note. It almost feels as though he misjudged the amount of his writing and suddenly reeled it in. The character of Plumptree serves no real purpose after his final appearance, the final confrontation is rushed and inorganic, the attack on Smith could be so much more better described, and worst of all – for this cozy, character-driven piece – there is no real resolution with the main characters (Did Hastie – as would be fitting – marry Lee’s sister? How did Lee recover? What of Long Norton? Under what circumstances did Bellingham leave? What did Plumptree think of the whole matter? What about Styles?).

I have often felt my brow knit and my pulse increase once I get to the climax, and have regretted the fact that Doyle wrote such a weak ending to a short story that may have been better served in novel form. But these are merely my complaints and we must move on and accept the past as set in stone. “Lot No. 249” remains – in spite of its faults – a beautiful narrative rich in setting, mood, character, and subtext, and is perhaps the seminal literary treatment of mummy fiction – as foundational to the genre as Dracula or Frankenstein are to theirs.

The Egyptological craze of the nineteenth century was still burning hot after its commencement with the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799, and would continue to blaze until World War II. Egypt represented something dearly coveted by the Victorians and the Edwardians. It was a grand society of passionate, elegant people, more ancient than Rome, nobler than Greece, more mystical than Babylon, and after Doyle’s brace of stories, fantasy and horror writers began to plumb its depths for material. Bram Stoker, E. F. Benson, H. P. Lovecraft, Robert Bloch, H. Rider Haggard, Agatha Christie, Ray Bradbury, Sax Rohmer, and Anne Rice generated fantastic tales surrounding animated mummies, haunted Egyptian relics, revived curses, and ghostly pyramids. Doyle’s hand, unquestionably, was in some way present in all of these works.

At the bottom of his tale, however, is the unavoidable conflict between Smith and Bellingham, and with it come questions which are both uncomfortable and fascinating to a modern audience. There is no question that we rebuke his portrayal of effeminate men as either domineering villains or submissive cowards, his depiction of British manhood as an ideal, or his suggestion that masculinity is a precious commodity not to be polluted with transcultural cross-pollination, but we must remember that the time in which he wrote was one of deep concern and uncertainty for the British male. As colonial projects continued to yield stories of atrocity, rebellion, and shame, and as domestic scandals such as the Cleveland Street debacle, the Oscar Wilde trial, and the exploits of crossdressers Fanny and Stella, long held assumptions of the superiority, nature, and definition of British manhood suddenly became elusive.

Today we applaud the blurring and – as it were – queering of such antique prejudices, but at the time it was an understandable crisis. The Big Brother of British colonialism (as seen in our next story, “The Brown Hand”) had reigned without question for several decades, but by the 1890s it was clear that Anglo-Saxon colonizers had ruined many of the cultures they sought to civilize, had spread disease and misery, and had been the agent of abuse and genocide. This was the case in Egypt just as it was in South America, India, and China. H. G. Wells, Joseph Conrad, Sir Roger Casement, and other disenchanted Victorians filled the papers, magazines, and bookstores with tales of colonial negligence, and the myth of the White Man’s Burden began to sour in the minds of the British public – and with it their assumptions about British manhood, for if Father truly knew best, then why were his Indian servants dying of cholera, and why were they being mutilated by his overseers, and why did they want to murder him in his bed?

Doyle’s tale responds with a comparatively light-handed description of noble masculinity: it need not be domineering or authoritative, but it should be robust – well-rounded, physically and mentally stable, and hardy to the core, without pretense, dependence, or intrigue. To him, the most stable form of manhood was that which was self-reliant and idealistic, excluding what he saw to be clingy neediness (a la Lee) and jaded jealousy (a la Bellingham). Today his estimation seems chauvinistic and heterosexist, and indeed it is. The mummy could be seen as the manifestation of homosexuality: a dark and frightening secret hidden in a closet and released at dark to dominate and “unman” its male victims, and in our society homosexual intercourse is not viewed as sodomy so much as love.

But to Doyle it may be less a parable about sexual deviancy (indeed, as much as our modern eyes recognize the tropes of homoeroticism, Doyle may have been horrified at the suggestion) as it is a simple discourse on what makes an adult male a productive member of society: a person who is strong-willed but compassionate, bold but gentle, idealistic but restrained, imaginative but logical, and balanced equally between the physical and mental experiences of life – neither a roughhousing bully nor a socially detached bookworm. Regardless of gender, class, income, sexual orientation, nationality, or religion, these are the hallmarks of a good citizen of the world, and they needn’t be a “robust,” British, white, Christian male to achieve what Doyle has so carefully described here.

And you can find our annotated and illustrated collection of Doyle's best horror stories HERE!